Mental health is not a given for anyone, it takes work. In fact, as Scott Peck, author of The Road Less Travelled, states, “…most of us are mentally ill to a greater or lesser degree.”

Sometimes people are depressed because they are not writing, dancing, singing, acting, starting a business, or fulfilling themselves in other ways they find meaningful. Should they be medicated? It might be better to find that thing that will put them back on track with their lives.

You Are Not Helpless

A lot of people who follow politics and world events experience depression and helplessness. A certain amount of this suffering may be thought of as healthy—that is, there may be real concern for the planet, the economy, the safety of themselves and others, and the stability of future generations. Being concerned, worried, frightened, etc., is not always a sign of mental illness. It can be a sign of awareness. For instance, if you are walking down a dark alley in a sketchy part of New York and experiencing anxiety, that might be a healthy, self-preserving voice saying, “Get out of the alley!”

Learned helplessness is a deeper, more problematic version of suffering. Learned helplessness is a term used in psychology to identify a perception in a person’s mind that leads them to believe that they are helpless to effect significant change in their life when faced with challenges. The person suffering from learned helplessness tends to blame the outside world for their problems. They often feel like a victim, become paralyzed in the face of decision-making, have little ability to problem solve big issues, etc. This can lead to a myriad of issues. They can be long suffering under the “safe” umbrella of a corporate job. They may often suffer from what’s called analysis paralysis - continually weighing the pros and cons of a decision so long they take no action. They can idle in fear of making the wrong decision while opportunties pass them by. Depression, isolation, withdrawal, substance abuse, or passivity my rear their ugly heads when a person with learned helplessness is faced with the need for change.

Learned helplessness is learned—usually from a repeated pattern of abuse or neglect early on. When a child is not given the ability to make any of their own choices, if they are severely criticized when making mistakes, if they are abused or abandoned - they learn that they have an“external locus of control” in their life. That is, their ability to exercise control when faced with challenges is outside of themselves (i.e. first located in the parents and later in the outside world). They come to believe that they are helpless—that life is happening to them from the outside world, not through their own decision-making and efforts.

These people often complain about how others are “taking their job,” or “getting all the breaks.” They exert little effort for change, take few risks, fee stuck in depression and stagnation, compulsively play the lottery or gamble to “strike it rich”, hope to be saved, etc.

The classic image of learned helplessness is the image of the caged bird. Having grown up in the cage the bird comes to believe there is no hope of flying. One day the cage is opened. The bird, trained to be helpless, stays in the cage thinking it has no other choice. Many of us are in a cage with the door open wondering how we can escape.

The positive side of having an “external locus of control” is that these same people will often share their successes with the efforts of others on a team effort. They are able to see others abilities and bless their efforts, they can be humble when they achieve goals.

A person with an “internal locus of control” believes that their life is essentially an effect of their own efforts and talents. These people tend to be supported in their decision making in childhood. They are often encouraged to make age appropriate decisions, they are supported to try again in the face of mistakes, they are allowed to explore beyond the family in a safe way. People with an “internal locus of control” believe their life is created through them, not to them. They tend to be self-starters, don’t complain about others, and take a hundred percent responsibility for their lives. As a result, their lives tend to be more productive and satisfying. When they are faced with a challenge their thinking is more along the lines of, “What did I do wrong, and what do I need to do to change this?” Their anxieties tend to be put into action.

The music producer and co-founder of DreamWorks, David Geffen, says that as a child is mother told him he had hands of gold and that he could do anything. She called him, “King David.” The film director Orson Wells reports that his parents said everything he did was wonderful, better than they had seen anyone do before him. The enslaved Harriet Tubman somehow believed she could still master her own life and was a founding member of the underground railroad to freedom. When Oprah Winfrey was told by her grandmother to watch her do laundry because one day she too would be maid Oprah says she quietly thought, “No, I’ll never be a maid.” All these people entered the world with an internal locus of power believing they could create what they wanted through their own efforts.

The shadow side of someone with an internal locus of control is that they can be narcissistic or self-negating. They may believe their team won or lost solely because of them. They can downplay the efforts of others. The are often overly critical of themselves even when events are outside of their control.

While we need personality traits that come from both the internal and external locus of controls, people with learned helplessness (having an external locus of control) tend to suffer more in life. They are often in need of getting the help, support, and nurturing they missed in childhood to reclaim their power.

Even if brought up with learned helplessness we can shift the locus of control from outer to inner. We might get involved in organizations, marches, or actions that help us feel empowered. We might go back to school, risk starting a buisness, take an art or acting class. Even small actions such as giving donations can help the psychological feeling of having power to influence our own thinking and world.

If you suffer from learned helplessness it is nothing to be ashamed of. It is a wound, not an irreparable damage (which you may believe from a helpless mind set!). You can find the help you need in therapy, support groups, reframing your thinking, taking small risks, and being encouraged to reclaim your power.

In her book, Feel The Fear and Do it Anyway, Susan Jeffers writes that at the bottom of every great fear is the belief that “I can’t handle this.” She advocates that, no matter what the challenge, begin with telling yourself, “I can handle it.”

While we all have both internal and external beliefs about where our locus of control is in life, we tend to default to one or the other in the face of challenges. Below is an explanation of how this may affect your work life.

Take a look:

There's Nothing Wrong With You

All of us have trauma we carry from childhood. We may have been adopted, left alone too much, from an alcoholic family, from smothering parents, the child of a divorce, an abusive family, a poor family, a drug addicted family, parents that valued money more than love, we may have had no family–having been passed around multiple foster homes, a homophobic family, a neglectful family . . . the list goes on.

As John Bradshaw, author of Homecoming, reminds us, “All families are dysfunctional to some degree.”

As a reality check, if you made it to adulthood and are reading this, your family also had a lot of stability and love. They should be honored for their gifts as much as questioned for their shortcomings.

When we internalize our family’s dysfunction, we come away with a core belief that, “something is wrong with me,” or, “I’m not enough”- not smart enough, good looking enough, athletic enough, talented enough, rich enough, outgoing enough, intelligent enough, black enough, white enough, tough enough, etc.

This “not enough” belief is also full of should stories. “I should be better, better looking, faster, smarter, more disciplined, more relaxed. I should be funny, white, straight, tall, sexier, shorter, heavier, thinner, cooler.” This internal story goes on to conclude that if I achieve what I “should be” then I’ll finally be “enough.”

Together these beliefs and stories set up a no-win situation in our minds and the way we live our lives: A belief that I’m not good enough but will be enough when I fulfill my corresponding “should story,” leaves me in endless catch 22 situations—never feeling enough, but always believing it is just around the corner when I meet another goal of the “should story.” As a result I can suffer from depression, anxiety, and fears of all kinds. The resulting dilemma is an inner psychological construct with a voice that tells us to seek full acceptance and love, but never find it.

For example, say my story is that I’m not enough because I don’t have money but I will be enough if I become rich. Low and behold I make it— I become rich. While this will act as a panacea for a short time, because I was trying to compensate for a lie to begin with, it won’t fix the core problem—the mistaken belief that something is wrong with me and it needs to be fixed.

Remember, there is nothing is wrong with you!

Your value as a human being is innate. There is nothing you need to do outside of yourself to achieve it. This is why we are so drawn to observe children and their innocent, open hearted approach to themselves and others. They have yet to learn any stories about being not good enough. They are expressing their true nature, something most of us have lost touch with.

The movie Citizen Kane is a story of a man who gained money and power to compensate for being abandoned in childhood (all children conclude that the reason they are left or abandoned by parents is that they are somehow not good enough.) When the character of Kane achieves great wealth and fame he feels great importance for a time in his life. However, he eventually falls into despair, realizing his solution didn’t work to cure the underlying sense of loneliness, fear, and being “not enough.”

There are many solutions to this dilemma. Self-Compassion and Mindfulness are two great methods (see previous blogs). Many of us also need a Psychodynamic approach – being mirrored by another person with unconditional acceptance.

One goal in therapy is to develop an unconditional positive regard for ourselves. When this is achieved we heal and return to the open heartedness of childhood—but this time with the maturity of an adult.

These internal “not enough stories” can be extraordinarily persistent—leading us into deep despair, doubt, addictions, and ongoing relationship issues.

If we don’t get help with our “not enough stories”, we may spend our entire lives unconsciously avoiding the actual solution to genuine happiness—as is told in Citizen Kane.

Is your belief of being “not enough” holding you back? Are you stuck in self-doubt, relying on an addiction, keeping yourself endlessly occupied with work, money issues, parenting duties, internet, talking, business, entertainment, etc.—so as not to feel the underlying emptiness? It is very normal to have this internal drama. Everyone I have met has some version of it. The courage to get help can be all it takes to break through to your authentic life, and your authentic happiness.

As Blaise Pascal, a French philosopher once famously said, “All of humanity’s problems stem from man’s inability to sit quietly in a room alone.”

We can suffer many abandonments early on. John Bradshaw writes at great length about the “abandoned child” inside of us—the one who didn’t’ get the attention, safety, love, admiration, nurturing, or encouragement they needed when they were at their most vulnerable.

In Citizen Kane, two scenes, one in the beginning of the film, and one at the end, exemplify the abandonment issue the central character suffers from throughout his life. After his parents abandon him early on, he internalizes a belief of being “not good enough.” He then spends his life trying to prove to others that he is “enough.” The only problem is that, while he attains more success than anyone around him, he never faces the internal pain. As a result, it festers like an unattended wound.

Kane looks in all the wrong places to find his worth—to money, women, power, etc.— but he never takes the deep journey inside, through the pain and back to the authentic, joyful, “inner child” who was left so early on.

When after all his attempts fail and his wife leaves him, triggering the deep unresolved abandonment wound, and "not enough" issue, he has a nervous break down.

That is, he seeks for love, but does not find it.

Take a look:

BE A REAL MAN

BE A REAL MAN

What the hell does that mean—be a real man? Historically it has meant things like: sacrifice yourself, take care of others, don’t feel, be competitive, win don’t lose, destroy your opponent, don’t trust, go numb in the face of pain, and above all, don’t be vulnerable. It often included being hard drinking, hard fighting, and promiscuous.

With Robert Bly’s groundbreaking book, Iron John, that kind of definition was drawn into serious question. Bly started men on a path of examining the value of their father’s way of being, and why they themselves felt so adrift, lonely, and lost as men.

Bly states that a boy needs to see his father, spend time with him, and witness the father’s work. When the father leaves in the morning, comes home late, is irritable or abusive from an inability to deal with the demands put on him, and retreats from the family—the son is lost. A hole opens in the son’s psyche and fills with suspicion about who men are and what he is to become.

Bly goes on to say that women have tried to compensate for the lack of the father to no avail. They can’t do it. Why? Because they’re women, not men. The mother has an opposite role of the father. Her role is to take in, nurture and protect the son in kind of safe, soft, loving embrace. The father’s role is to transmit a different kind of love. The father’s love is direct, assertive, loving, but with an edge that teaches the son to cut away from the dependency bonds of the mother and to come into his own powers as a man. Both are equally valuable, but with the advent of the industrial and information ages, the distance between father and son has become so great, the father’s teachings often get lost.

Bly goes on to explain that a kind of psychic food passes from father to son when they spend time together in a safe, committed way. The son learns to trust his masculinity, his ability to problem solve and make decisions, and his healthy warrior—a ferocity that is both nurturing and empowering.

When the father is absent or dangerous or both, the son tends to cling to the “mother’s world”, the only place of safety. This leaves the son in a terrible state, unable to move forward, and without the help he needs to “break out of the mother’s orbit and enter the world of men.” He may remain a child in many ways: unable to make decisions, staying near the family when he has opportunities to make his own way, feeling perpetually victimized, lacking the steel in his character that will help him cut through the difficulties of life, falling into addictions of all kinds, etc.

Historically tribal cultures understood not only the need for the fathers at home, but the necessity of ritual to inform the son of how to transition from boyhood to manhood. Boys would be taken away from their mothers to islands where they were initiated into the society of men.

Without these rituals many men are stunted in their psychological development. The shadow side of this inability to develop can be deeply dangerous: dictators, corporate executives who ignore the environment (the Dakota Pipeline comes to mind), addicts, wall street bankers who gamble with the nation’s economy, and war mongers are just a few examples of the kind of men who come about when not given the help to access their mature masculinity. In essence, they are frustrated, scared children in adult bodies.

Another form this lack of ritual can take is what Bly calls, the "soft man." This man is overly sensitive, afraid to assertive himself, and compassionate with others to the point of impotentence. He lacks the reslove, steel, and fierceness of the warrior. He often regards anger as dangerous and is quick to sacrifice himself. He might ask the question, "Why don't I get what I want when I'm so nice to everyone?"

Today men are getting smarter. Men’s retreats are being held throughout the world to help men repair and regain the lost teachings of their fathers. In these retreats men learn to trust the love of men, to risk with each other, to regain their warrior spirit, and to honor the earth. Bly himself did these retreats for many years in Minnesota. Today Mankind Project (mankindproject.org) leads retreats and offers ongoing support for men who are struggling to make their way in the world. Therapy can be a way to regain the teachings of men, especially group therapy. Below is an interview done by Bill Moyers (a man with mature masculinity as a journalist) with Robert Bly.

Take a look:

YOU ARE A HERO

Picking up on last week’s post, lets explore what Joseph Campbell meant when he said we are all on the “Hero’s Journey.” Campbell coined the term Hero's Journey after studying myths from cultures around the world. He found that all cultures explain the challenges, pitfalls, and accomplishments of life as being essentially the same.

The Hero’s Journey through life has challenges that we will either meet and overcome, or we will meet and be defeated by. It does not matter how small you think your life is. Campbell says that Einstein, Joan of Arc, a shoe salesman, and a garbage collector are all on the same Hero’s Journey.

The Hero’s Journey is not a one-time trip. We all have a journey to leave the world of dependency and create our own independent life (or remain forever adolescent in our approach to adult living—the “eternal child syndrome”). We sometimes have a Hero’s Journey through the long, painful road out of an addiction (or as they say in recovery circles—end up in death, jails, or institutions having been defeated by the challenge.) We have a Hero’s Journey into our life’s authentic work—that which brings us fulfillment, accomplishment, and contribution (or we end up defeated and embittered in a dead end job, feeling trapped in work we took up solely for money, or without work at all.) We may have the Hero’s Journey of raising children successfully (or in the tragedy of abandoning our children after bringing them into the world).

We could have the journey into marriage, creating a business, entering a spiritual discipline, or starting a charity. Every major life adventure has the qualities of what Campbell calls, The Hero’s Journey. Often times the journey is more internal than external. You may suffer in a challenging marriage, or resist relationship altogether. You might be secretly in dire financial trouble, or struggling to get a business off the ground. The doubt, fear, courage, risk taking, and help we experience on the journey are all under our influence. How we manage them will determine how our journey turns out.

The journey has specific stages. Let’s use Star Wars, a classic story of the Hero’s Journey, to outline the stages Campbell defined:

1. Ordinary Life: Our day-to-day life that feels safe but unchallenging. Luke is initially living a mundane day-to-day existence. He wants to be a pilot but clings his known, safe home.

2. Call to Adventure: The hero is faced with something that calls him to begin his adventure. Luke finds a holograph message in R2D2 from Princess Leia asking for help.

3. Refusal of the Call: The hero attempts to refuse the adventure because he is afraid. Luke’s initial reaction is to say “Look I can’t get involved. I’ve got work to do. It’s not that I like the Empire. I hate it, but there’s nothing I can do about it right now.”

4. Meeting with the Mentor: The hero encounters someone who can give him advice and ready him for the journey ahead. Luke meets Obi-Wan Kenobi who shows him his father’s light saber and eventually acts as his mentor. (In the next film he also meets Yoda as a mentor / guide).

5. Crossing the Threshold: The hero leaves his ordinary world for the first time and crosses the threshold into adventure. Luke’s aunt and uncle are killed and he leaves to help Princess Leia. His first stop is Mos Eisley’s Cantina where he sees characters from across the galaxy that have been into the far reaches of their own journeys.

6. Test, Allies, Enemies: The hero learns the rules of his new world. During this time, he endures tests of strength of will, meets friends, and comes face to face with foes. Luke meets allies Han Solo and Chewbacca. When he tries to leave the planet Tatooine, storm troopers attempt to stop him. He succeeds in his escape and is on the way to Alderaan.

7. Approach: Setbacks occur, sometimes causing the hero to try a new approach or adopt new ideas. Luke discovers that Alderaan has been destroyed. It has been replaced by The Death Star. Fear and doubt return. Luke: “I have a bad feeling about this.”

8. Ordeal: The hero experiences a major hurdle or obstacle, such as a life or death crisis. Luke rescues Princess Leia but witnesses the death of Obi-Wan in the fight.

9. Reward: After surviving death, the hero earns his reward or accomplishes his goal. Luke emerges from his ordeal as an adult hero and joins the rebel fleet as a pilot.

10. The Road Back: The hero begins his journey back to ordinary life. Luke has a way back to normalcy by leaving the upcoming conflict and escaping with Hans Solo. He decides to join the rebellion.

11. Resurrection Hero: The hero faces a final test that brings all he has learned to his life challenge. Luke destroys the Death Star in a climactic battle. He learns to trust The Force and comes into his own powers.

12. Return with Elixir: The hero brings his knowledge back to the ordinary world where he applies it to help all who remain. Luke returns, is celebrated in a ceremony, and gives hope to his community that they will survive the Empire with fighters like him.

The story of the Hero’s Journey is told over and over in our culture. Your life, as much as anyone else’s, is an example of either the triumphs or the pitfalls of your own Hero’s Journey. It is hard wiring we are all born with. In fact, your journey from embryo to birth is your first Hero’s journey (and a journey for the mother).

If you feel at a loss about the importance or success of your own Hero’s Journey, perhaps you are stuck in the stage of Resisting the Call. Is there a book you are resisting writing? Is there a job you should be going for? Are you holding back from asking her to marry you? Are you afraid to let go of a high paying job to enter your true calling? Is it time to move? Are you wallowing in an addiction and resisting getting help?

Help is available for you in many forms to progress on your journey. Therapists, sponsors, business mentors, coaches—what kind of help or mentorship do you need to move into your full journey?

We are all on the Hero’s Journey whether we want to admit it or not. That is why Hollywood keeps telling the same stories in different forms such as The Wizard of Oz, Harry Potter, or Star Wars— and why we resonate with them.

Check out this link and you’ll see what I mean:

You Are In Star Wars

Carl Jung, a Swiss psychologist and protégé of Sigmund Freud, broke with Freud when he presented the idea that we all draw our awareness from a “collective unconscious.” In essence, according to Jung, while it seems we have separate minds, we are actually all part of one universal mind. Within this one mind he stipulated that we share archetypes.

Archetypes are universally shared ideas, patterns of thought or images. These energies are at play in our consciousness and up to us to harness and utilize in an effective way to bring about our destiny and self-actualization.

While we all have each of the twelve major archetypes within us as part of the collective unconscious, some archetypes play a major role in our personality while others remain in a relatively minor capacity. Which ones play a major role in your personality? The 12 major archetypes in Jungian psychology are:

The Innocent: The Innocent is naïve and childlike. Its motto is: be free to be you and I’ll be free to be me. Goal: be happy and enter paradise. Fear: being wrong and being punished. The Innocent tries to do everything right as a way of feeling safe. Weakness: it can be boring in its simplicity. Talents: faith and optimism. Examples: R2D2, The Doorman, The Car Washer, The Waiter, The Bartender. Innocents tend to play simple but important roles in society relieving the seriousness of life and bringing childlike wisdom to it. They rarely become famous due to their low-key nature. Being There was a 1979 Peter Sellers movie in which he plays an Innocent whose occupation is that of a gardener. The character turns out to be Christ-like figure advising the U.S. president.

The Orphan: Motto—All people are created equal. Goal: belonging. Fear: abandonment, being left out, standing alone in a crowd. Strategy: develop ordinary, solid virtues, be down to earth, and have a common touch. Weakness: blending in for the sake of superficial relationships. Strength: realism, empathy, and lack of pretense. Examples: Harry Potter, The Lion King, Luke Skywalker, and Oliver Twist….another famous orphan liked baseball: Babe Ruth.

The Warrior: Motto—Where there’s a will, there’s a way. Core desire: Prove worth through acts of courage. Goal: mastery in a way that improves the world. Fear: weakness, vulnerability, being viewed as afraid. Strategy: be as strong as possible. Examples: Lawyers, Hilary Clinton, Luke Skywalker, President Obama, Princess Leia, Steven Spielberg, Oprah, Harvey Milk, David Geffen, and Nelson Mandela.

The Caregiver: Motto—Love your neighbor as yourself. Core desire: to protect and care for others. Goal: help others. Great Fear: selfishness, ingratitude. Strategy: doing things for others. Weakness: martyrdom and being taken advantage of by others. Examples: C-3PO, Chewbacca, Mother Theresa, Nurses, Doctors, Social Workers, and Martin Luther King.

The Explorer: Motto—Don’t fence me in. Core desire: freedom to find out who I am through exploration. Goal: experience a better, more fulfilling life. Fear: being trapped, conforming, inner emptiness. Strategy: journey, seeking out and experiencing new things, escape from boredom. Weakness: aimless wandering, becoming a misfit. Talent: autonomy, ambition, being true to self. Examples: Han Solo, Astronauts, Amelia Earhart, Eleanor Roosevelt, Jacques Cousteau.

The Rebel: Motto—Rules are made to be broken. Core desire: revenge or revolution. Goal: to overturn what isn’t working. Greatest fear: to be ineffectual or powerless. Strategy: disrupt, destroy, or shock. Weakness: crossing over to the dark side. Talent: outrageousness, radical freedom. Examples: Luke Skywalker (and the “Rebel Alliance”), Darth Vader, Fidel Castro, Muhammad Ali, the Arab spring.

The Lover: Motto—you’re the only one. Desire: intimacy and experience. Goal: being in relationship with the people, work, and surroundings they love. Fear: being alone, unwanted, unloved. Weakness: pleasing others while at risk of losing own identity. Talent: passion, appreciation, gratitude, commitment. Examples: Florists, Bakers, Mothers, Princess Leia, Luna Lovegood from Harry Potter, The Phantom from Phantom of The Opera, Glen Close in a shadow form of the Lover in the movie, Fatal Attraction.

The Creator: Motto—If you can imagine it, it can be done. Core desire: create things of enduring value. Goal: realize a vision. Greatest fear: mediocre vision of execution. Strategy: develop artistic control and skill. Task: create culture, express vision. Weakness: perfectionism, bad solutions. Examples: Steve Jobs, Henry Ford, Picasso, George Lucas, people developing new Apps, artists of all kinds.

The Fool: Motto—You only live once. Core desire: live in the moment and enjoy life. Goal: have a great time and lighten the world. Fear: being boring or bored. Strategy: play, make jokes, and be funny. Weakness: frivolity, wasting time. Talent: joy. Examples: Jar Jar Binks, Robin Williams, Pee Wee Herman, Sarah Silverman, Joan Rivers, your friend whose always making fun of your seriousness.

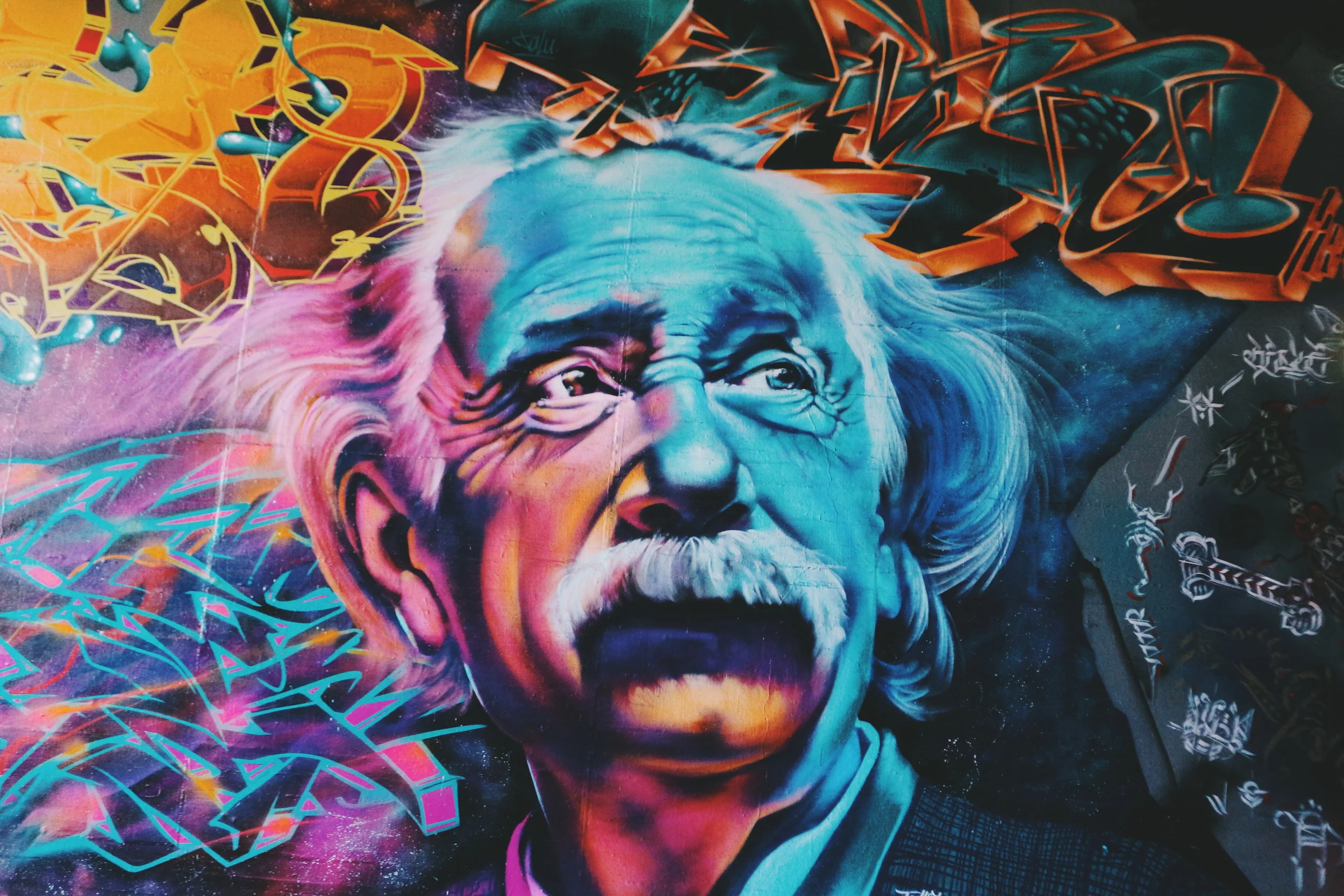

The Sage: Motto—The truth will set you free. Core desire: to find the truth. Goal: use intelligence and analysis to understand the world. Biggest Fear: being duped, mislead, or being ignorant. Strategy: seeking out information and knowledge, self-reflection. Weakness: can study details forever and never act. Talent: wisdom. Examples: Yoda, Obi Wan Kenobi, Einstein, Albus Dumbledore, Aristotle, any number of homeless philosophers mumbling in the streets.

The Magician: Motto—I make things happen. Core desire: understanding the fundamental laws of the universe. Goal: to make dreams come true. Fear: unintended negative consequences. Strategy: develop a vision and live by it. Weakness: becoming manipulative. Talent: finding win-win solutions. Examples: Emperor Palpatine (shadow), Carl Jung, therapists, shamans, doctors, Nikolas Tesla, the creators of the atomic bomb (shadow Magician).

The Ruler: Motto—Power is the only thing. Core desire: control. Goal: creates a prosperous family or community. Strategy: exercise power. Fear: chaos, being overthrown. Weakness: authoritarian, tyrannical. Talent: responsibility, leadership. Examples: Pres. Obama, Fidel Castro, Darth Vader, Corporate executives, Mark Zuckerberg, Donald Trump, Saddam Hussein.

As you recognize your primary archetypes, what others remain undeveloped? Is your Ruler too tyrannical? Do you need to give the Lover more time in your life to balance the Ruler? Is your Caregiver too self-sacrificing? Do you need to develop more Warrior energy to assert yourself? Is life stagnated? Do you need to feed the Creator or Explorer in order to expand? Each of us shares all archetypes from the collective unconscious. Understanding which are strong, which are weak, and which are in shadow (destructive form) can help to understand how to better organize your approach to healing, achievement, and fulfillment.

George Lucas famously incorporated archetypes from Jungian psychology and the work of Joseph Campbell (a friend of Jung and author of The Power of Myth) into his Star Wars saga.

There was a recent app on Facebook that, if you entered in your character traits, would identify what character you would be from Star Wars. That is, it would tell you what your primary archetype is.

Below is a clip from Star Wars where Campbell reflects on the archetypes and what he coined, the “Hero’s Journey”— a psychological journey through the archetypes we all must either choose to take, or refuse to take—and go to the “dark side” (i.e. the shadow form of the archetypes). Will you be Luke Skywalker and take the journey, or refuse and end up holding hands with Darth Vader?

Check it out:

DEPRESSION, ANXIETY & THE VOICE IN YOUR HEAD

The “voice in the head” is a conditioned sub-personality or false self. It is conditioned from all your positive and negative experiences from the past. Its commentary is usually laced with some degree of fear. It often talks like your parents or like someone who raised you. It uses your own voice to convince you it is you. It is almost always generating some degree of fear, anxiety, depression, or anger.

I CAN'T GET THEM OUT OF MY MIND

Love Addiction is a mysterious, painful kind of addiction that affects millions of people. Love Addiction is when someone feels they are actually addicted to another person. What? You can get addicted to a person? Yes, you can. The definition of an addiction is when a substance, activity or person makes your life unmanageable.

SUFFERING - A TEACHER FOR EVERYONE

WHO LET THE DOGS OUT?

When our lives are a mess it's common to look around for someone to blame. We tend to ask: How did this happen to me? How did I become an addict? How did I lose all the money? Why did he leave? Why am I sick? Why am I being evicted? How did this business deal get so messed up? How did this affair happen? How did it get so out of control? Why am I so alone? In other words, Who let the dogs out and made such a mess of things? The answer, fortunately or unfortunately, is you did.

SO YOU WANNA BE RICH?

There’s an old joke that goes, if you ask someone if they masturbate there are two kinds of people who answer— those that say yes, and those that lie. The same is usually true about asking someone if they want to be rich—there are those that do, and those that lie. When we think about it, why wouldn’t someone want access to unlimited resources to be able to make their life and the lives of many others better? Why would we not want abundance for ourselves and to share with the world? Why would we not want to be rich?

THE SEXUAL AROUSAL TEMPLATE

VICTIM, WARRIOR & 100%

“Life is difficult. This is a great truth, one of the greatest truths. It is a great truth because once we truly see this truth, we transcend it. Once we truly know that life is difficult - once we truly understand and accept it - then life is no longer difficult. Because once it is accepted, the fact that life is difficult no longer matters….Most do not fully see this truth that life is difficult. Instead they moan more or less incessantly, nosily or subtly, about the enormity of their problems, their burdens, or their difficulties as if life were generally easy, as if life should be easy….Life is a series of problems. Do we want to moan about them or solve them?”

LOVER, GENIUS & CRAB

When we don’t give the Lover Archetype the positive channel it craves, the Lover does not go away, it goes “Shadow.” The Shadow Lover is also interested in creating, but it creates from a negative, self-destructive place. The Shadow Lover saturates our sensuality from an over indulgent and even dangerous place.